I’m a couple days late for Coming Out Day, but I know you always enjoy my reflective writing.

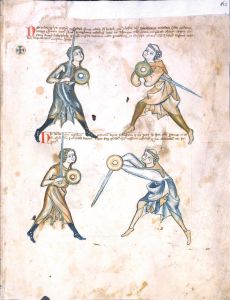

People have been asking me lately when I’m going to give a presentation about historical swordswomen again. And… I wasn’t really planning to. But I think it’s probably time to reexamine that choice.

There are a lot of reasons I haven’t felt excited about going back to it. When I was working on updating and expanding it, a bunch of stressful stuff was going on in my life, including a lot of tension and frustration with someone who was working on the project with me. Going back to the subject feels too much like going back to all of that, to the extent that I’ve never put it on my Lectures and Recordings page.

But the reason that comes into my mind first is, that’s not what I want to be famous for. I don’t want to be remembered as the woman who works on woman stuff. Historical swordfighting is a very male-dominated space, and I’ve been navigating that my entire adult life, trying to find the right amount of “remind the men that people who aren’t men exist and are different” and trying not to worry about “they won’t take me (or maybe any woman) seriously if I’m not man enough.”

So… I have this presentation I don’t want to be famous for, but it’s already something people remember about me and, more importantly, want more of. Which I guess means I have an opportunity to reshape their perception.

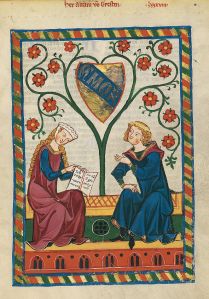

And it’s information that needs to be put out into the world again, because for the love of kittens, “cool non-man swordfighters” does not begin and end with La Maupin and basically none of those meme pictures are actually of her anyway. And also her story usually has wacky exaggerated genderfuckery fingerprints all over it, like some 18th or 19th century person said “aha, a story with non-mainstream gender and sexuality! Allow me to impose some of my ideas about gender onto it to make sure you notice gender things are happening but also reassure you that women are ladylike and attracted to men!” Like the bit where she stabs a guy in a duel but then tenderly nurses him back to health before having sex with him. Or the thing where her early serious relationship with a woman is only discussed as the framing for why she set the convent on fire and is otherwise elided to a couple sentences.

I guess I have more to say about this topic.

So.

The world needs me to share more information about individual non-men fighters, and probably also broader categories of non-men who were doing combat and defense stuff, and point out that a lot of the gender division ideas we modern folk have about the medieval era were given to us by the historians of intervening centuries.

And I need to find ways to do that– all of that– without feeling like I’m compromising my own priorities for presenting my identity to others.

I think the first step to making it manageable is to separate it into two topics, because I think it would be difficult and also unhelpful to simultaneously cover “binary gender has been imposed onto history in weird ways” and “gender and sexuality are not binary.” Taken separately, I think each of those topics fits better with the current Darth Kendra brand than the old presentation does.

I suspect a lot of you are now wondering, Darth Kendra, what do you want to be famous for? Because, you’re right, I shouldn’t define myself by what I don’t want. And I think if I have to boil it all down to one single idea, that idea is READ ALL THE MANUSCRIPTS. I don’t want to be remembered as the person with all the ladies in armor pictures, or the merfolk pictures, or even as the Florius translator– I want all of those to be taken together to create a big picture of “Darth Kendra will read everything unstoppably when she’s on the trail of something interesting, and then (sooner or later) share the journey and also the discovery at the end.”

While I’m talking about ways I intend to be more out and true, I’m resolving to put more stickers on my HEMA gear. I think– I’m trying to believe– that using my gear to celebrate some things I love, and thus share a little more of my truer self with everyone I fight, will make me stronger and healthier. Even– or, no, especially– if some of those things are definitely not manly, like glitter pastel cottagecore and fluffy cats sitting by rainy windows.